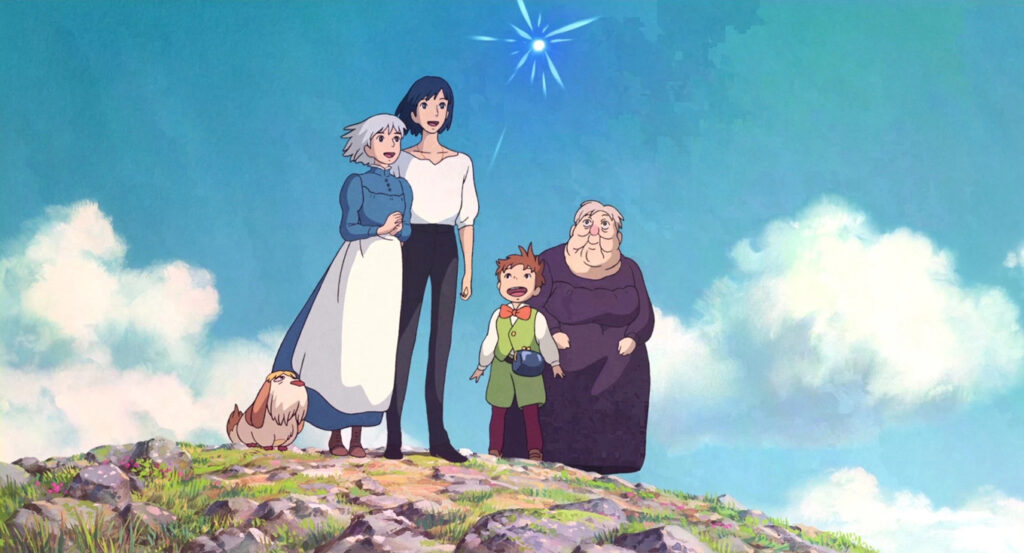

This is a screenshot from Howl’s Moving Castle. The characters, from left, are Heen the dog, Sophie, Howl, Markl and the Witch of the Waste.

By Lindsay Steele

Now Streaming

Howl’s Moving Castle (Studio Ghibli)

Genre: Animated, fantasy/adventure

Streaming service: Max

Rating: PG (mildly frightening images)

Summary: When a spiteful witch curses an unconfident young woman, giving her an old body, her only chance of breaking the spell lies with a self-indulgent, insecure young wizard and his companions in his legged, walking castle.

Reflection: As a ‘90s kid, the release of a new Disney movie was a special event. Mom and Dad would drive my sister and me to the nearest theater for an afternoon showing. We’d munch on Mike and Ikes candy while watching fantastical stories like Beauty and the Beast and Aladdin come to life on the big screen.

I feel a deep nostalgia for animated films but realize now that I wasn’t seeing the whole picture. Halfway across the world, Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki was creating Totoro, Ponyo and a host of other lovable characters. The Japanese studio rivaled Disney in quantity and quality of work during my formative years but it wasn’t on my radar until the studio’s latest release, “The Boy and the Heron,” began to generate Oscar buzz on social media. My husband, Chris, enjoys Japanese animation, so he was happy to pick up a few Ghibli DVDs during his weekly trip to the library. We have since subscribed to Max (formerly HBO Max), where all but one Studio Ghibli film is available to stream.

My first entry into the Ghibli collection was an English dub of Howl’s Moving Castle. Released in 2004, it features the voices of Christian Bale, Jean Simmons and Lauren Bacall. I was drawn to the film’s whimsical 2D animation and director Miyazaki’s ability to weave multiple layers of meaning into a deceptively simple story. I watched the film several times in an effort to understand it fully.

What fascinated me most was the portrayal of the villain as redeemable. In most animated fantasy films, a clear distinction exists between good and evil. The protagonist(s) must extinguish the villain to earn a happy ending. In “Howl,” the villain’s redemption is part of the happy ending.

The Witch of the Waste is the primary antagonist. She has an obsessive crush on a handsome wizard, Howl, and makes herself appear youthful and glamorous in hopes of attracting his attention. The witch sees Sophie as a romantic threat and curses her with an old woman’s body. Sophie never considered the possibility that Howl might be interested — she has always seen herself as plain and unworthy — so she is frustrated that the witch seemingly cursed her for no reason. “Wait until I get my hands on her!” Sophie declares.

One might expect the film to end with the witch’s defeat and in the film’s source material (a book of the same name by Diana Wynne Jones), it does. However, Miyazaki offers a different solution. When the witch loses her powers and becomes physically disabled midway through the film, Sophie doesn’t gloat. She feels compassion for the witch and takes her in. Over time, they develop a family-like bond and a mutual respect for each other.

Perhaps it would have been easier for Sophie to leave her antagonist to die but her counterintuitive action leaves room for everyone to grow, including the witch, Howl and herself. The film’s happy ending depends on it.

I have since watched other Studio Ghibli films created under Miyazaki’s direction and it seems this treatment of villains is a hallmark of his work. He imagines worlds in which people are flawed, but peace is possible. I suspect it may be his way of dealing with the trauma he experienced as a child during World War II, which he has been open about throughout his career. He saw first-hand how war hurts people on both sides, regardless of who wins.

Ancient Shinto tradition and his Eastern upbringing often inspire Miyazaki’s works, yet his message of forgiveness and nonviolence is something we can all take to heart. The Lord’s Prayer states, “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Miyazaki shows us why vengeance is not the answer. Through his films, he re-imagines a world in which compassion wins.

Discussion questions:

What did you find most touching about this film?

Would you have made the same choice as Sophie? Why or why not?

What does our faith teach us about war, nonviolence and forgiveness?

(Editor’s note: Lindsay Steele is a reporter for The Catholic Messenger. Contact her at steele@davenportdiocese.org or by phone at (563) 888-4248.)