By Celine Klosterman

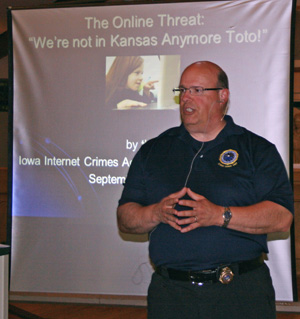

BETTENDORF — Online exploitation of minors is a problem in Iowa, and parents are on the front lines of defense, a criminal investigator told about 75 people at St. John Vianney Church Sept. 10.

Over two hours, Michael Ferjak of the Iowa Department of Justice discussed online predators, cyber-bullying, sexting, and the potential dangers children face in social networking, email, chat rooms and other online communications.

He shared news reports of Internet sex stings and cases of child exploitation. “People ask all the time: Does this happen in Iowa? Yes, it does.” It occurs in all states, Ferjak said.

In a 2010 survey of 1,501 youths ages 10-17, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children found that within their first year online, one in five had received an unwanted sexual solicitation. Girls were targeted at twice the rate of boys. But 49 percent of the youths told no one about the contact.

“I believe we know only 10 percent of what’s going on out there,” said Ferjak, senior investigator with the Iowa Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force.

Each time a website that sexually exploits youths is shut down, 10 more pop up, he said. “We’re not going to arrest our way out of this problem. That’s why we’re doing outreach and education – to reduce the target pool.” Parents and other adults need to help young people make good decisions regarding online safety.

But only a third of homes with Internet access have software that blocks objectionable online content, Ferjak said.

Computers appeal to sexual predators because the technology offers anonymity, an unsupervised environment, instant gratification, and the ability to identify potential victims anywhere, especially on social networking sites. A list of people registered with the social networking website myspace.com included more than 100,000 registered sex offenders, he said.

Predators seize on the personal information and photos that youths often post on such sites. “These guys do their homework,” Ferjak said.

Password-protect your wireless Internet signal, he advised. If neighbors connect to your signal and download child porn, law enforcement will trace that activity back to you.

Also problematic is cyber-bullying, the use of the Internet and mobile devices to harass, embarrass, threaten or isolate people. Some studies suggest this doesn’t happen often, but Ferjak said that’s because youths don’t often report it.

He shared stories of youths who committed suicide after being bullied online. “We’ve had deaths in Iowa as a result of this.”

Monitor your children’s email accounts and social networking activity, he advised parents. Encourage youths to tell you if they feel threatened. If you suspect bullying, talk to the source of it, seek legal assistance, discuss the matter with your child and turn off the computer. Victims should not reply to harassing messages, but should preserve evidence and report the activity.

Some teenagers also are “sexting,” or sending sexually explicit photos and messages via cell phones and other technology. “The vast majority of these cases come out of a boyfriend/girlfriend thing,” Ferjak said. A boy may ask his girlfriend to send him a photo of herself; later he’ll send it to his whole baseball team. Many youths don’t realize that taking, sending or possessing explicit photos of minors – even of themselves — is a crime of child pornography, he said.

Tackling such problems takes vigilance on everyone’s part — including families, schools and law enforcement, Ferjak noted.

Bishop Martin Amos and Alicia Owens, victim assistance coordinator for the Diocese of Davenport, urged attendees to spread the word. “Take this information home, do something, and then come back together,” Owens said.

For more information, visit the Iowa Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force website at www. iaicac.org or www.netsmartz.org.