By Father Thom Hennen

Question Box Column

Q. How should I respond to a grieving family member who wants the cremated remains of a loved one placed in a special container to be displayed in their home or incorporated in jewelry or other objects as a remembrance?

A. This comes up frequently and it seems there are many more options for this sort of thing than ever before. Losing someone is difficult and so it is certainly understandable why those who are grieving would want some tangible remembrance of their loved one. I think this speaks to a sacramental sensibility in all of us. We are body-soul creatures. We interact with each other and with the world around us through our bodies and physical senses. This is why as Catholics we don’t just sit in a quiet, bare room and think about God as our worship. Rather, we walk, sing, sit, stand, kneel, splash ourselves with holy water, anoint people with oil, use incense and offer bread and wine in the sacrifice-meal that is the Eucharist. Even Jesus cured by making mud from dirt and his own saliva and smearing it on the eyes of the man born blind, then had him wash in the pool of Siloam (John 9:6-7). He could just have easily said the word and made it so.

At the same time, the practices you mention may also reflect beliefs that are contrary to our understanding of Christian anthropology and our belief in the resurrection of the body. On the one hand, these practices might reveal a dualistic approach to human nature, seeing the person as only the incorporeal soul and the body as little more than a “container.” Even so, we knew the person through the “container,” so we might like to hold on to some aspect of their physical being.

On the other hand, such practices can reveal a kind of extreme physicalism or materialism that sees the human person as only their body or physical nature. Accordingly, if this one life and our physical bodies are all that we have, then we will cling to them all the more, even after death.

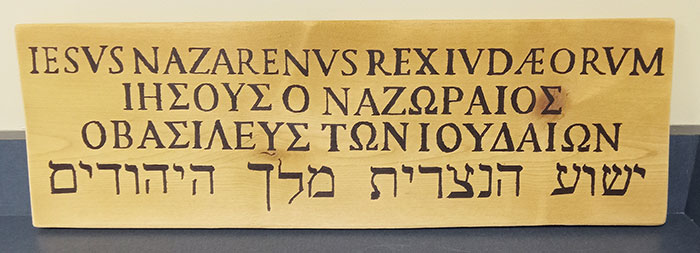

I don’t think most people want such a remembrance of their loved one to fall into either of these categories. Still, I think we need to be careful. The reason the Church insists on proper burial of the body or cremated remains is rooted in our profound respect for the body, even in death, and because we believe in the resurrection of the dead. How this will play out largely remains a mystery, but Jesus’ own resurrection give us some clues. First, it is truly a bodily resurrection. He still bears the wounds of his crucifixion and he eats in front of his disciples to prove that he is not a ghost (Luke 24:39-43). Second, his is a glorified body, not simply a reanimated corpse. This is not “Zombie Jesus.”

Catholic practice on the proper treatment of the body in death, therefore, needs to respect the integral whole of the human person as body and soul and should reflect our faith and hope in the resurrection of the body.

In March the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Doctrine published a statement entitled “On the Proper Disposition of Bodily Remains.” It addresses some of these practices, including new developments such as alkaline hydrolysis and human composting, neither of which are permitted.

As to that desire for a tangible remembrance, I think this can be fulfilled as easily and meaningfully through a picture or some other memento and with greater respect for the deceased.

(Father Thom Hennen serves as the pastor of Sacred Heart Cathedral in Davenport and Vicar General for the Diocese of Davenport. Send questions to messenger@davenportdiocese.org)