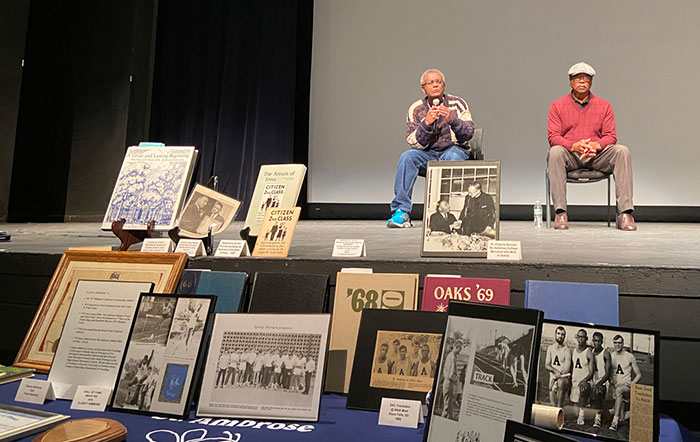

Jim Collins, left, and Clancy Simmons, both graduates of St. Ambrose College (now university) in Davenport, participate in a Q&A session following the Jan. 26 showing of “The Loyola Project’ in SAU’s Galvin Fine Arts Center. Another free showing is Feb. 4 at 3 p.m. at the center.

By Barb Arland-Fye

The Catholic Messenger

DAVENPORT — Watching “The Loyola Project” documentary about the 1963 Loyola University Chicago Ramblers basketball team that broke racial barriers was both entertaining and disturbing, said Clancy Simmons, a 1971 graduate of St. Ambrose University who is Black.

He viewed the video at his alma mater along with fellow alumnus Jim Collins (SAU, Class of ’69) and a wider audience, many of whom were white. For many in the audience, the documentary underscored the complicated issue of racism.

Collins and Simmons, track athletes at SAU who went on to distinguished careers, stayed for a Q&A session after the Jan. 26 showing of The Loyola Project in the university’s Galvin Fine Arts Center. A second, free showing is scheduled for Feb. 4 at 3 p.m. at Galvin.

Notre Dame Club of the Quad Cities, the event’s sponsor, invited Collins and Simmons to participate in the Q&A after each showing of the 2022 documentary to spark meaningful conversations about racial discrimination.

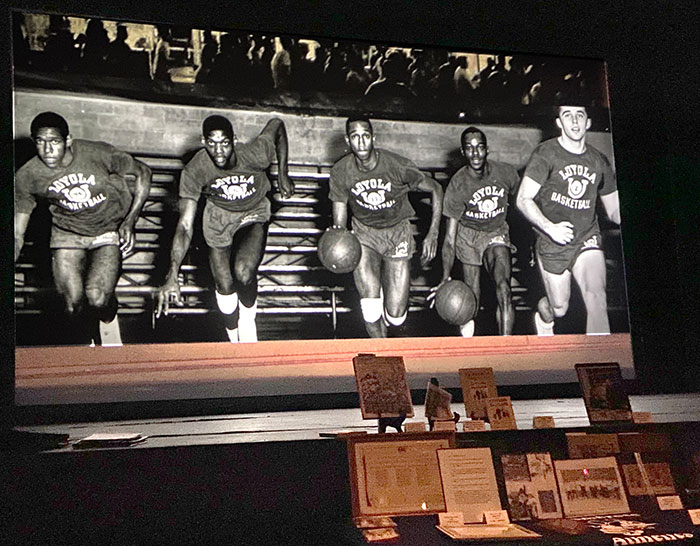

Photos, film clips, artist’s renderings and interviews with some players from the 1963 team and their competitors underscored the complicated struggle with racism during a watershed time in the civil rights movement. Loyola’s Coach George Ireland took an unprecedented move in starting four Black players, which led to a nail-biting NCAA championship in 1963.

“This team not only revolutionized the way college basketball was played, but also battled and overcame extreme racism both on and off the court,” a promotional brochure states. However, the Black players at times feared for their lives and endured “unwritten rules” regarding treatment of the races. The documentary also leaves lingering questions about Coach Ireland’s motives.

During the Q&A Jan. 26, Collins and Simmons spoke about their experiences at St. Ambrose College (now university). There were just a handful of Black students on campus then, but the number has grown substantially, said Collins, who married the love of his life while in college. “I wanted to make the world better and to make it better for my family.” The college, in turn, supported him every step of the way. He realized that while he was raising a family, his university family was raising him.

Simmons recalled a childhood memory, sitting with his brother on a curb outside their apartment house across the street from Central High School in Davenport. “Thirty years later, I would be principal of that school. Who could have known? I just needed an opportunity.” He received that opportunity at St. Ambrose, but at the same time realized the awesome responsibility of needing to set an example for his family and the Black community.

Addressing a question about the “unwritten rules” of discrimination referred to in The Loyola Project, Collins and Simmons gave examples from their experiences growing up in the Quad Cities. Collins referred to one “Five and Dime” store’s policy, which allowed Black persons to purchase food but not consume it on the premises. Other examples included housing discrimination and the hurtful exclusion from a college friend’s wedding because Collins’ wife, Karen, is white.

“This place was no different than any place else in the 1960s,” Simmons said. He recalled one stinging moment when, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, he could hear cheering on campus. He, too, spoke of housing discrimination. “We (Black people) were not allowed to buy anything north of Locust Street (in Davenport).” He spoke of feeling troubled by “the appalling silence” of the good people who do not speak up when they witness racism. Watching (The Loyola Project) brought it all back for me.”

Audience reaction

Bishop Thomas Zinkula attended the Jan. 26 showing of The Loyola Project and said he was aware of the story but “appreciated the opportunity to hear more about it, including from some of the

Members of the Loyola University Chicago Ramblers basketball team appear in this clip from the documentary “The Loyola Project.”

players themselves. I thought the documentary was well done. I had assumed that the coach was the main protagonist of the story, in the sense that his primary motivation in recruiting and playing more Black players than other colleges and universities was because of a concern about racism, trying to break it down. I was surprised to discover that in reality it appears that he was mostly concerned about winning games and protecting his job.” As for the appalling silence of the good people, Bishop Zinkula said, “Catholics refer to this as the sin of omission.”

Thomas Mason IV, who chairs the St. Martin de Porres Society of Sacred Heart Cathedral in Davenport, thought the movie was excellent. “But at the same time, I found certain aspects bone-chilling. For example, when the team went to Louisiana to play Loyola-South and another college offered to house the team so that they could all stay together in the segregated South. However, Coach Ireland still separated the team by allowing the white players to stay in hotels and sent the Black players to Algiers Parish, which is predominantly black, to be with people of their own skin color. In my opinion, the team never should have been separated when they had the option of staying together.”

Mason, an SAU graduate who is Black, said Collins and Clancy “did an excellent job of sharing their collegiate athletic experiences with the audience. We saw through the lenses of a non-traditional, married student and a traditional student who lived on campus. Although their experiences varied while they were in college, they each had a positive one and after graduation, they each went on to remarkable professional careers where they enriched the lives of the many they encountered.”

Kevin O’Brien of Davenport described the documentary as important because “It tells the story of how the Black players went through so much that their white coach and teammates were oblivious to or weren’t interested in learning.” The Loyola Project caused him to reflect on “how often we look at the civil rights movement as history and not still something we are in the middle of. There shouldn’t be an end date…. We have a complicated history,” he said. “It’s important not to whitewash it.”

“To think that so much racism and discrimination ever existed is disturbing,” said Eileen O’Brien, Kevin’s mother. “Progress has been made, but we still have a long way to go.” One instance that stood out for her in the well-done documentary was the game Loyola played against Houston (in Houston). “It was shockingly clear that the black players’ lives were in jeopardy as they played basketball.”

She said the comments of Collins and Simmons afterwards “added a local dimension to it, both growing up in the Quad Cities and going to St. Ambrose. Clancy Simmons quoted Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. about the ‘Appalling silence of the good people.’ That moved me and I am still thinking about that.”