By Dan Ebener

(Part one of a three-part series)

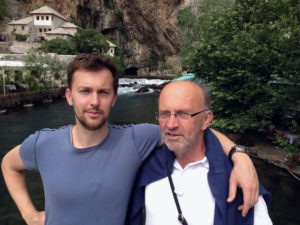

Teaching in Croatia for the past six years, I have developed friendships that allow for some very interesting discoveries about life, culture and religion in that part of the world (see photo). The following article is based on conversations with friends in Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia.

Estimated at 90 percent Catholic, Croatia is one of the most Catholic nations in the world. But being Catholic in Croatia means something entirely different. In Croatia, as in Bosnia and Serbia, being Catholic is more of a “nationality” than a religion.

Understanding this distinction helps explain why churches in Croatia, as in most of Europe, are so empty. To be Catholic in Croatia does not necessarily mean you ascribe to a certain creed. It does not mean you practice a certain faith. It does not even mean you belong to a certain religion.

Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia have been at the forefront of many wars and the target of numerous empires such as the Roman, Venetian, Turkish, Austro-Hungarian and Russian. To discuss this history with locals, you get the impression these events are current. The effects are current. Collectively, these empires still impact national boundaries, language, food, currency, culture and religion.

Each empire brought its own “religion” with it. Before the Turks conquered much of the area in the 16th century, most people were Roman Catholic. For the Croats, the important moment in history occurred when they stopped the Turks before they could reach Zagreb, their capital. But just to the south in Bosnia, the Turkish Empire brought a new religion. At that point, in order to work any job connected with the government, or start a new business or get any political favors, you had to become a Muslim.

The Turkish conquest explains much of the division that remains in Bosnia to this day. But that division is not necessarily religious. During the Turkish reign, families were divided. In the same family, some brothers, sisters or cousins might convert to Islam while others remained Christian. They were still family to each other. They shared the same blood lines. To describe this division hundreds of years later as racial, ethnic or religious is misleading.

Rino Medic and his father Damir Medic visit a Muslim shrine in Mostar, Bosnia.

Fast forward to World War II when several countries, including Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia, became what was called Yugoslavia. In 1971, Josip Tito, as dictator of Yugoslavia, declared that the country had three “nationalities:” Croats (mostly Roman Catholic), Serbs (mostly Orthodox Christian) and Bosniaks (mostly Muslims). In the eyes of the locals, religion became a nationality. It had little to do with creed, faith or what we would call religion.

A philosophy professor at the college where I teach in Zagreb conveyed this story about his daughter, who asked her dad, “If we are atheists, why do I need to be confirmed Catholic?” He explained that “the only true atheist is a Catholic atheist.” To him, being Catholic was a nationalist concept and to be naturalized as such, you went through the Catholic Church.

A Muslim professor agreed with this logic, explaining that he and his family have never practiced Islam. But being Muslim is a central factor in his identity. He described himself as a “Muslim atheist.” He added, “I don’t know the first thing about practicing the Muslim faith but I would die for the right to be a Muslim.”

Viewing “religion” in this way — as national self-identity, not a practice of faith — helps explain a lot about life, culture and religion in Croatia. It also explains why religions that profess to be about peace and love can be seen as the driving force for warfare.

In my next installment on this series, I will describe the situation in Mostar, Bosnia, a place where Croat Catholics, Bosnian Muslims and Serbian Orthodox are trying to live in peace, 20 years after a bitter war that almost destroyed the city and the country.

(Dan R. Ebener teaches at St. Ambrose University and serves as diocesan director of Stewardship and Parish Planning.)

What percent of people in Croatia are catholic?

I am looking for information on the Workers Rosary,which now is the peace Rosary in Medjogre and thru the world.I am presenting in the school of prayer the peace Rosary which I am told began in Croatia appx 100’years ago.Any insights or web sites you can offer for research would be greatly appreciated.My presentation us May 22

Try doing a Google search on Medjugorje.