By Barb Arland-Fye

FORT MADISON — Inmates dressed in fresh T-shirts and blue jeans enter the snug chapel at Iowa State Penitentiary for a rare opportunity: Mass with a bishop. Warden Nick Ludwick has just introduced himself to Bishop Martin Amos, thanked him for his presence and recited from memory a Latin phrase he recalled from his days as an altar boy in Michigan. Grinning, the bishop responded in Latin.

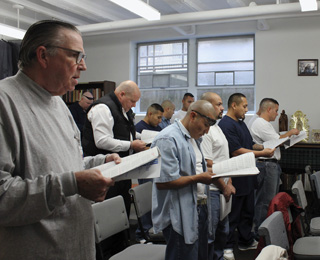

A videographer and sound man arrive to videotape the bishop’s visit. As the 21 inmates walk into the chapel, Ludwick asks, “Do you guys mind being filmed?” Depending on their responses, he points to chairs in the back, middle or front of the room. Bishop Amos, wearing purple vestments and holding his shepherd’s staff, greets the inmates. One asks how the bishop is doing. “I’m doing fine; how are you?”

Bishop Amos may be the first bishop to celebrate Mass inside the prison which opened in 1839, seven years before Iowa became a state. As shepherd of Catholics in southeast Iowa, the bishop notes that “this is certainly my parish, and these are my parishioners, too.” He’ll likely be the last bishop to preside at Mass in the prison that predates invention of the electric light bulb. The old prison is poised to close, and the 620 maximum security inmates will move into the new prison in March. The videographer and sound man are recording the transition, and received permission to videotape Bishop Amos’ Dec. 4 visit as part of the project.

Some of the inmates have lived in the old prison for 20, 30, 40, or even 50 years; many are serving life sentences. “Most of the men serving life are serving it for murder,” says Deacon David Sallen, a member of Holy Family Parish in Fort Madison who leads a monthly Communion service at the prison. He organized the bishop’s visit with support from the warden and Associate Warden of Treatment Mike Schierbrock, and other staff.

“I’ve been explaining to (the inmates) that they’re part of the universal Church and that our bishop is a successor of the apostles, and that’s one of the marks of our Church,” Deacon Sallen explains. They said, ‘Well, we want to have him come.’ I said I would work on it. The next time I saw Bishop Amos I asked him if he’d be interested in coming and he said sure.” Planning began six months ago.

Pointing out the significance of the bishop’s visit to the inmates, Schierbrock said: “I tried to explain it’s not very often 20 or 30 people will get a Mass with a bishop. And it’s the last time here.”

Inmates invited to this Mass had a prerequisite: attendance at Mass in November. Priests of the region take turns presiding at the monthly Mass here. One of them, Holy Family Pastor Father David Wilkening, is concelebrating today’s Mass; Deacons Sallen and David Montgomery are assisting.

The Catholic prisoners won’t have their own chapel in the new facility; they’ll share an all-faith chapel with other denominations — Protestants, Jews, Muslims and even Satanists. The large crucifix displayed here in Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, along with pictures, statues and other symbols of Catholicism will have to be put up and taken down for each Mass in the new facility.

But today inmates, staff and volunteer prison ministers focus on this celebration of the Eucharist and the annual (early) Christmas dinner for chapel members to be shared afterwards. Before Mass begins, Deacon Sallen introduces Bishop Amos. “… He has come to break bread with his church in captivity,” the deacon says.

Ludwick sits in the middle row next to Schierbrock, surrounded by inmates. “I’m also part of this (prison) community,” the warden explains after Mass. “I’ve never been a desk jockey. Wardens can’t run prisons from their desks. We’re a community within walls … and I just happen to be the mayor.”

When people ask Ludwick why he has spent his career in corrections, he says: “Someone has to look out for all of God’s children.” That includes the men housed in this prison, who are some of the most “problematic individuals” in the state’s corrections system. The warden never forgets that these men have victims. Nonetheless, “you have to care about people. It’s our job to run a safe, secure and humane facility. We don’t try to distance ourselves (from the inmates).”

Schierbrock tells offenders when they enter the Fort Madison prison that they’ve already been punished by being sent here. “Our job is not to punish; our job is to manage you and to help you … our job is to turn out better citizens.”

An inmate named Lha approaches the lectern to proclaim the first reading, from Isaiah, which he reads with confidence and feeling. After Mass, he notes, “It’s always an honor when you have people coming from the outside.” He appreciates being able to attend Mass here because “I feel connected; (we’re) coming together for something meaningful.”

After Lha returns to his seat, everyone waits expectantly for someone to lead the responsorial psalm. A minute or two passes. Inmate Enrique gets up from his seat and bashfully approaches the ambo, just inches away from where Bishop Amos is sitting. “I’m from Mexico, and my second language is English,” Enrique says after Mass, apologizing for what he deems to be a less-than-perfect reading of the responsorial psalm. Bishop Amos assures the 35-year-old inmate that he did just fine.

In his homily, Bishop Amos focuses on Advent themes of waiting, hope and mercy, and how the faithful ought to live their lives in this in-between time of Christ’s incarnation and his second coming at the end of time. It is a time of grace, but also a time marked by a struggle, the bishop says: “between darkness and light, flesh and spirit; the part of us that is redeemed and the part not yet redeemed; violence and peace; between this age and the age that is to come.”

The videographer later asks the bishop whether he had intentionally focused on time because the prisoners are serving time. “No,” the bishop says. “The Scriptures opened that up for me.”

Bishop Amos had envisioned his audience and what he might say to them as he prepared his homily, he told The Catholic Messenger in a separate interview. “I didn’t want to say anything wrong, and at the same time, I wanted to challenge them. I knew that my example had to fit people who couldn’t just go out into the world, people who were not going to be leaving this institution. It really had to relate to them.”

After exchanging the sign of peace with one another, inmates walk up to the bishop to extend the sign of peace to him. “Every time we have Mass everybody shares the sign of peace with everybody else, including the visitors and the celebrant,” Deacon Sallen says. Extending peace to the bishop “shows the spirit of welcome they have for him.”

It is a moving experience for Bishop Amos, he reflects afterwards. “It’s like Communion; it’s one of those times when you can look at someone’s face and see a genuine smile.” In another prison where he celebrated Mass, prisoners were not allowed to exchange the sign of peace.

Immediately following Mass, an inmate named Fred says a prayer of thanksgiving for celebration of the Eucharist with Bishop Amos, for the volunteer prison ministers who visit monthly and for the feast that all are about to eat.

Jean Gunn and Karen Ruble have been volunteering in prison ministry for several years; Karen worked in the prison’s health care unit as a registered nurse before retiring in 2009. Russell Savage is a newcomer to their prison ministry group. All are members of Holy Family Parish in Fort Madison.

“When I go home, I feel so fulfilled,” Gunn says. “I feel good coming up here to support these fellows. They’re so glad you come.” Ruble appreciates being able to speak freely about her faith and to share it with the inmates. “To have the bishop here today,” Ruble says, “is wonderful,” interjects Gunn.

Inmates, staff, clergy and volunteer prison ministers exit the chapel and walk down the hall into a larger room that serves as the Protestant chapel. Today it functions as a banquet hall.

“This is quite a feast you have,” Bishop Amos says, sitting down at a table laden with pizza, chicken, fresh shrimp, bags of chips and large grapes, containers of beans and cold salads. At another table, inmates work enthusiastically preparing fresh ingredients for tacos. Money for the meal comes from their savings and a contribution from the volunteer prison ministers’ small fund.

At Bishop Amos’ table, Enrique shares stories about his family in California and talks about his work taking care of prisoners who can no longer care for themselves. He bathes them, changes their diapers and attends to other needs.

“Just think, you’re being a Mother Teresa,” volunteer prison minister Ruth Coffey exclaims.

“The Lord gives us grace, even here in prison,” Deacon Sallen observes.

“I was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Enrique says, explaining why he is in prison. “I’m in a place where I can help somebody.”

Like the other inmates, Enrique expresses appreciation that Bishop Amos has taken time out of his busy schedule to share Eucharist with them and to participate in their Christmas feast. “We feel blessed that he is here. We were happy because we were going to have a banquet, but having a bishop here was a plus. It was better than Christmas.”

I live in Bettendorf, Iowa. I have 2 children at home, and two grown. I run a church library (St. Pius X, Rock island) I have several boxes of good Catholic books, that we already have copies of in our church library — could they be donated to a prison such as this?

Also, do you know what are the opportunities for prison/jail ministry near Bettendorf? I have done door to door ministry with the Legion of Mary (again in Rock Island) but I have not done much volunteer work for several years.

My husband and I have been married for 34 years, and still going strong.

Susan Wanke