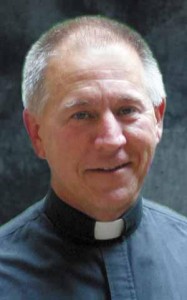

By Fr. Bud Grant

The Advent Scriptures have begun to shift in tone away from intensely apocalyptic images. The messages of the Gospels are of repentance from sin (Mk. 1:4) and expectation of the eminent arrival of the Messiah (Jn. 1:7, 27).

These help re-frame the conversation of a Christian “green eschatology” away from global destruction to hope of rebirth, supporting a thoroughly biblical environmentalism. They do not anticipate an ultimate end, but a renewal. This squares well with Jesus’ self-understanding as a prophet calling the House of Israel to its own best vision of itself: humans are part of nature, all of which is “groaning as if in labor pains … for redemption.” Creation, even if once “slave to corruption” and “subject to futility,” is to enjoy a “share in the glorious freedom of the children of God” (Rom. 8:20-23).

But this shift to a “gentle apocalypse” does not permit us to dodge the implacable anti-earth sentiment reflected in the second reading for the second Sunday of Advent from II Peter 3. “… the heavens will pass away with a mighty roar and the elements will be dissolved by fire…” (verses 10, 12).

Among the interesting details in this passage is the enigmatic exhortation that the faithful ought to be found “waiting for and hastening the coming of the day of God.” This is exactly the sort of phrase that David Horrwell sees as encouraging Christian fundamentalists to interpret “natural disasters and signs of earthy decay as indicators of the imminent end which are … to be welcomed” (The Bible and the Environment, 16).

In his brief book, Horrwell provides an impressively analytical summary of environmental biblical scholarship. Demure in offering many conclusions of his own, though sympathetic to their efforts, he dispassionately critiques theologians’ — sometimes clearly overly enthusiastic — attempts to “green” the Bible. In the case of II Peter his judgment is instructive and sobering, even if not particularly cheering for those of us who insist that saving God’s creation is intrinsic to biblical faith.

“It seems,” he summarizes, “that the biblical texts leave us with an uncertain and ambivalent legacy when it comes to the possible contribution of their future visions to theological and ethical views of the environment” (ibid 113). Thus, as in the case of, say, feminist biblical interpretation, some passages are helpful, others, to say the least, are problematic.

And for environmental theologians, II Peter 3 is just that, a problem. Put simply, II Peter stands as an obstacle to a pro-earth biblical faith. It was written in a time of intense persecution of Christians by the hegemonic society of Rome; it echoes the suffering of those who, despite that persecution, have remained faithful; it explains the delayed parousia as God’s merciful forbearance designed to engender repentance. All this mitigates the otherwise lurid tone of expectation that unbelievers will finally “get theirs.” But none of this completely deflects the vivid images of a burning earth.

In short, we are presented with an uncomfortable but important reminder that the fabric of the Bible is woven of many diverse strands, that there is theological variety among the human contributors to the corpus. The author of II Peter, clearly influenced by Greek and Roman philosophy, literature and mythology, may well be the last person to contribute to the New Testament, even later than Revelation. The letter constitutes a blunt instrument in addressing the problem of theodicy, that is, the question of why the good suffer while the wicked prosper, with an assertion of delayed but inevitable divine retribution.

Even given all this, we are left with a simple fact: he envisions the end of the world as God’s punishment, not the renewal or salvation of non-human creation. In short, to quote the somewhat stoic philosophy of my students, “it is what it is.” The Gospel is certainly “green” but that doesn’t mean that every contributor to it is.

(Father Bud Grant is an assistant professor of theology at St. Ambrose University in Davenport.)