By Barb Arland-Fye

The Catholic Messenger

Three years before he was assassinated April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., received the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award in person from the Davenport Catholic Interracial Council. Nonviolence, he pointed out in his acceptance speech April 28, 1965, undergirds “all of our work” to ensure the dignity and human rights of every person. That approach was in line with the spirit of the award, he noted.

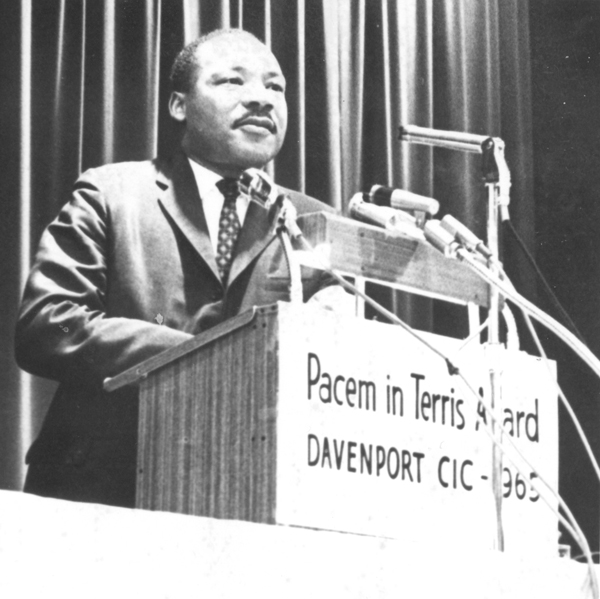

Martin Luther King, Jr., accepts the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award in Davenport on April 28, 1965. The civil rights leader was slain April 4, 1968, in Memphis.

“I am convinced that nonviolence is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and human dignity, and I accept this award tonight more determined than ever to commit myself to the fulfilment and realization of the philosophy of nonviolence and the philosophy of love.”

King, a Baptist preacher and recipient of the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, identified actions that people of faith, individually and collectively, could undertake to make the American dream a reality for all. He called for concern for the world dream of peace and brotherhood, reaffirming the immorality of racial segregation, the development of massive action programs to make justice a reality, and the use of legislation, marches, boycotts and other activities to bring about change.

The practice of nonviolence in effecting change is “as old as the insights of Jesus of Nazareth, and as modern as the techniques of Mohandas K. Gandhi,” King said. The idea of defeating one’s opponent was abhorrent. Changing the opponent’s heart was the goal.

“It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence, it’s either nonviolence or nonexistence,” King said. He was prescient about the suffering that would occur along the journey to a just and peaceful world. “Before the victory is won some of us will get scarred up a little; before the victory is won some will be thrown into jail; before the victory is won some will be called bad names, misunderstood; some will be called Reds and Communists simply because they believe in the brotherhood of man. Before the victory is won, somebody else may have to face physical death. If physical death is the price some must pay to free their children from a permanent death of the spirit, then nothing can be more redemptive.”

‘He preached the Gospel’

King practiced what he preached. His example of nonviolence and his words influenced and continue to shape the lives and ministry of Catholic leaders in the Diocese of Davenport.

“We were well instructed by priests on the faculty (of St. Ambrose College) about what was right and wrong as far as race was concerned,” said Father Michael Phillips, who as a seminarian listened to King speak that day in 1965. “I felt really good about that (social justice teaching) as I went on in ministry,” the retired priest added.

Three years later, when King was assassinated, Fr. Phillips was attending major seminary at Mount St. Bernard in Dubuque, Iowa. “We had a little prayer session in the chapel at Mount St. Bernard. Everyone was down. He (King) was the hope of the future as far as race relations. … He was a model for a lot of us, and a minister besides. So we had something in common with him. He preached the Gospel, and that’s what we wanted to do.”

In the 1980s, Fr. Phillips had the opportunity to give a sermon at a Baptist church in Davenport. He adapted his style to what he had witnessed in Baptist preaching. That energized the congregation, with people calling out, “Brother Mike, say it again; that’s the Word of God!” He felt a sense of brotherhood and love. Fr. Phillips said he learned from his parents about the equality of all people. That message was reinforced in the seminary and continues to inspire his relationships with others.

Father Walter Helms, also a seminarian at the time of King’s visit to Davenport, remembers getting his program autographed by the civil rights leader. King’s social justice message, reinforced by instructors at St. Ambrose College, shaped the future priest’s ministry. While serving in Muscatine, Fr. Helms said he worked closely with a Presbyterian pastor on racial justice issues. Now retired, the priest said he has a great appreciation for all that King went through, and his courage. “I still think in the long run — it’s easy to say and hard to do — nonviolence is still the answer.”

King provided example for nonviolence practices

As followers of St. Francis, peace and nonviolence are core values of the Sisters of St. Francis of Clinton. The example Martin Luther King, Jr., set in the civil rights movement helped the sisters apply those values in modern times. “Our whole journey as Clinton Franciscans to recognize, acknowledge and name our corporate mission as living and promoting active nonviolence and peacemaking has taken place within the life and death of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” observed Sister Jan Cebula, OSF, president of the Clinton Franciscans. King’s “efforts helped us to understand the message, really understand it, and the ways to put it into practice in our day and age.”

The sisters have participated in actions with other people, such as rallies, demonstrations and civil disobedience, and are engaged in advocacy and education in areas such as human trafficking, peace initiatives, affordable housing, feeding the hungry and more. King focused on issues and injustice, and not on denigrating people.

People tend to associate King exclusively with the race issue, and forget that nonviolence undergirded his work on all issues, Sr. Cebula said. In developing nonviolent strategies, she believes progress has been made in the 50 years since his death: restorative justice, the accompaniment movement (accompanying people in conflict-torn places to deal nonviolently with warring sides), peace teams and nonviolent civil protection. “A lot more needs to be done.”

Sr. Cebula sees great hope in efforts such as the student-led effort nationwide to address gun violence. “They are already applying some of the strategies of nonviolence. I hope that they will have mentors in how to apply more strategies (including social media).” The practice of nonviolence, as exemplified by King, requires education and transformation, she said.

An international movement called the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative aims to educate and transform, building support for integrating Gospel nonviolence throughout the Catholic Church. The initiative seeks a papal encyclical on nonviolence, or a synod, and further development of Catholic social teaching around nonviolence, Sr. Cebula said. The Clinton Franciscans and the Congregation of the Humility of Mary are exploring collaboration with the Diocese of Davenport on local efforts. “For we who are Christian and Catholics, it’s about helping people see that nonviolence was what Jesus was about.”

Fostering global solidarity

Sister Irene Munoz, CHM, was a young nun advocating on behalf of migrant workers when King was slain. His message resonated with her and continues to motivate her ministry. “I’m working with people who come from different countries, immigrants, and I’m more conscious of his efforts for civil rights and economic rights. We need to continue to honor that for all people.” She calls for affordable housing for all and a just living wage. “We need to foster a culture of global solidarity.”

The exodus of people from their homelands to the United States and other countries “is going to change our world,” she said. “When we begin to meet each other, that’s when we are going to say, ‘I can’t hurt my brothers and sisters of others nations and colors because I have learned to meet this one, this person.’” Immigrants and nonimmigrants learn from each other, she added.

In the Ottumwa area, where Sr. Munoz ministers, “we had a Filipino Mass, we had an African liturgy, and in so many ways it seems foreign. But you listen to the language and you think, this is about this creator, this God we all know…. They are people like us who want to live a good life, who have dignity and respect.”

She asks, “How can we love and serve each other and how can we learn diplomatic ways to relate to people who do not believe as we believe? We need to be open with that love God has shown us.”

That openness begins in the family. Their needs must be addressed so that they can thrive. And, she noted, “We can’t forget the whole racism issue. We still continue with racism in our being, and through the Spirit’s help, perhaps we can lessen it and hopefully eradicate it for good.”

Respect for one another

Jim Collins, a retired Deere & Co. executive who is black, thinks that people today focus on the negatives and fail to celebrate the achievements since King’s death. The Davenport Civil Rights Commission, for example, is planning a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Fair Housing Act on April 27. Topics to be addressed include civil rights and housing discrimination, economic privilege and racism, and the intersection of segregation in housing and education.

Project NOW Community Action Agency, which serves the Illinois Quad-City region, has its roots in an event called Sunday of Commitment organized shortly after King’s assassination at Rock Island (Illinois) High School Field House, Collins said. The agency helps families with low income and senior citizens to meet basic needs and achieve self-sufficiency.

“There’s a saying, a phrase, that came out of Dr. King’s legacy and it goes like this: ‘He changed the world and he never threw a brick and he never burned a building in order to make that happen.’ That goes to the premise of nonviolence,” said Collins, an active member of Sacred Heart Cathedral in Davenport. “It’s about my respect for you and your respect for me. Do unto others….”

Yes, people had to advocate and work to bring about change in unjust laws and policies. He recalls the effort required to change the exorbitant fee required for completing a complaint of housing discrimination, for example. He and his wife, as newlyweds in 1965, were denied housing in the west end of Rock Island, presumably because they were an interracial couple, he said.

“I think we have to come together because that’s what (King) did. We have to raise questions about continued areas of discrimination. But we have people in different areas of our community who clearly want to be divisive and it’s in their rhetoric and in their protests. I have nothing against protesting, but I’m saying, ‘Don’t just talk about it. Be about it. You work for the change, and you celebrate.”

Collins said that King did not want to be a civil rights leader, initially. “He was a pastor and that’s what he wanted to be.” But he was asked to lead a bus boycott seeking to change discrimination against people of color. “Sometimes folks just have to step up.”